UF researchers find changing gut microbiota, taming inflammation may help battle colorectal cancer

Colon cancer may be treated or even prevented by altering microorganisms in the intestine and by combating inflammation with a clinical treatment previously used to treat inflammatory bowel diseases, findings from a study led by University of Florida researchers suggest.

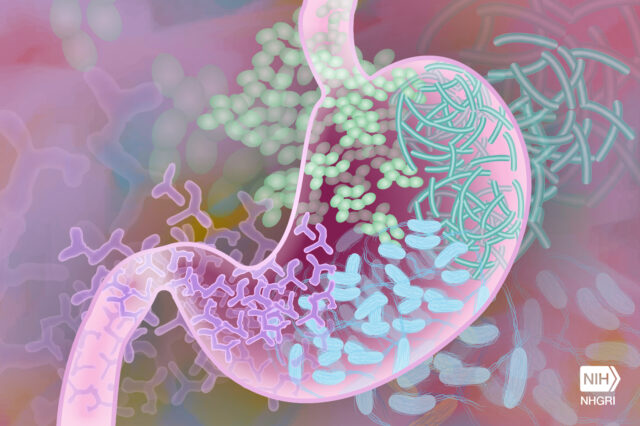

Inside a human gut resides trillions of microorganisms, which are collectively termed microbiota. Research has linked microbiota activity to a variety of diseases, from autism to cancer. Particularly in the gut, an abnormal microbiota can contribute to inflammation and colorectal cancer development.

“In this study, we really looked at the interaction between inflammation and cancer development, and how the gut microbiota is involved in this interaction,” said Ye Yang, Ph.D., lead author and an assistant scientist in the UF College of Medicine’s division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition.

Inflammation has also been shown to cause increased risk for cancer development, Yang said. Previous research has shown that people with inflammatory bowel disease have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer — cancer that occurs in the colon or rectum.

Yang and his team studied how combating inflammation using an anti-inflammatory treatment could affect colon cancer development in mice. Mice with colon cancer and inflammation were treated with an anti-inflammatory therapy known as anti-tumor necrosis factor, or TNF, therapy, which is a drug typically used to treat inflammatory bowel disease.

“We showed that if we gave mice this anti-TNF therapy, we could lessen the inflammation as well as colon cancer development,” Yang said. “We also found the composition and function of the microbiota changes a lot as a result of the treatment.”

The study found that after anti-TNF therapy, the microbiota was less capable of driving cancer development, Yang said. Therefore, reducing inflammation changes the microbiota from a pro-cancer to an anti-cancer state.

The next step for the researchers is to look for microbial genes or pathways that are regulated by anti-inflammatory agents and affect cancer development, Yang said. This study suggests further research needs to be done to understand interaction between certain therapies, the microbiota and cancer development.

“We need to pay more attention to the microbiota changes in response to inflammation-targeting drugs and figure out the best way to manipulate the microbiota for cancer prevention in patients,” Yang said.

This study, “Amending microbiota by targeting intestinal inflammation with TNF blockade attenuates development of colorectal cancer,” was published in July by Nature Cancer. It was co-authored by UF Health Cancer Center members Christian Jobin, Ph.D., co-leader of the UF Health Cancer Center’s Cancer Therapeutics and Host Response research program and senior author, and Raad Gharaibeh, Ph.D., director of microbial genomics with Rachel Newsome, a graduate student in the UF College of Medicine’s division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition. The study was funded in part by the UF Health Cancer Center and the National Institutes of Health.

Media contact: Ken Garcia at kdgarcia@ufl.edu or 352-273-9799.

About the author