UF Health researchers on team studying possible viral link with Type 1 diabetes

A prolonged infection by a common virus might sometimes trigger the immune system attack on the pancreas that ultimately leads to Type 1 diabetes.

The finding from The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young, or TEDDY, study was recently published in the journal Nature Medicine by a team of scientists that includes a University of Florida Health researcher.

By examining the stool samples of more than 8,000 children from the United States and Europe for the remnants of viral infections, researchers found an association between an infection of coxsackievirus for 30 days or longer and the development of the autoimmunity that can lead to Type 1 diabetes.

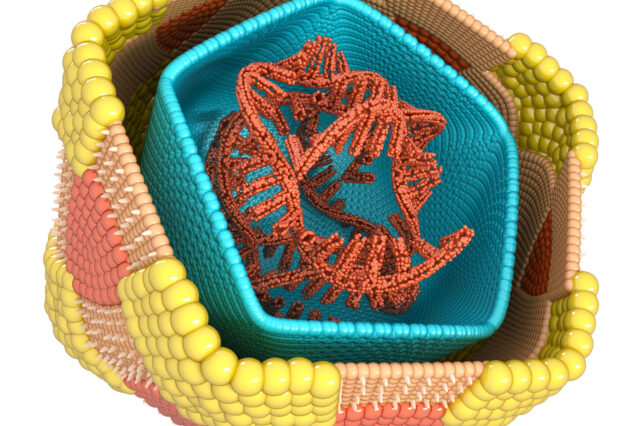

Such an autoimmunity means the body attacks the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas, which causes Type 1 diabetes. Insulin is a hormone that regulates blood sugar. Without it, the body cannot maintain normal blood sugar levels, which can lead to serious medical complications.

The study strengthens the case that the virus, long suspected as a trigger for that autoimmune attack, might be one cause of Type 1 diabetes, said study co-author Desmond Schatz, M.D., pediatric medical director of the UF Diabetes Institute and a professor serving as the interim chair of the UF College of Medicine’s department of pediatrics.

“The lamentation of where we are in research is that we don’t fully understand the mechanism leading to Type 1 diabetes,” Schatz said. “We know there’s not one cause of the disease. There are probably several. This brings us a step closer to possibly understanding one of those causes.”

The coxsackievirus, classified as an enterovirus and so named because it was first found in a patient from Coxsackie, N.Y., often leads to no symptoms at all in children, although in others it can cause mild flu-like symptoms. In most cases, the viral infection quickly disappears without treatment. But in others, it can lead to more serious illnesses, including meningitis.

“Down the road, if we were to eradicate this virus, such as with a vaccine or its early identification for those at risk, we might be able to prevent diabetes in some cases,” Schatz said.

TEDDY is a multicenter, multinational investigation designed to identify whether environmental factors such as infections, diet, stress or other conditions trigger the onset of Type 1 diabetes in genetically susceptible children.

TEDDY follows children from birth to the age of 15 at six clinical centers, including UF Health. The study is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and JDRF.

Kendra Vehik, M.P.H., Ph.D., the study’s lead author and a professor at the University of South Florida, said the study’s findings are important because enteroviruses are so common.

“Only a small subset of children who get enterovirus will go on to develop beta cell autoimmunity,” she said. “Those whose infection lasts a month or more will be at higher risk.”

Researchers also found that infection by another type of virus, adenovirus C, which can cause respiratory infections, was associated with a lower risk of developing the beta cell autoimmunity.

“Taking it all together, our study provides a new understanding of the roles different viruses can play in the development of beta cell autoimmunity linked to Type 1 diabetes and suggests new avenues for intervention that could potentially prevent (the disease) in some children,” said study co-author Richard Lloyd, Ph.D., a professor of molecular virology and microbiology at the Baylor College of Medicine.

Beta cells of the pancreas express a cell surface protein that helps them talk to neighboring cells. This protein has been adopted by the coxsackievirus as a receptor molecule to allow the virus to attach to the cell surface, researchers said.

The investigators found that children who carry a specific genetic variant of this virus receptor have a higher risk of developing beta cell autoimmunity and, ultimately, Type 1 diabetes.

“This is the first time it has been shown that a variant in this virus receptor is tied to an increased risk for beta cell autoimmunity,” said Vehik.

About the author