The innovators: How UF is using new technology to help patients and save lives

Miguel Acevedo spends a few minutes with his daughter, Sianna, in the neonatal intensive care unit at Shands at UF.

Kalipay Acevedo wasn't due to have her baby for another month, when one sleepy Sunday morning recently she felt her stomach drop. No pain. No contractions. She was just gushing blood.

Her husband, Miguel, called the ambulance to their Tampa home. Kalipay passed out on the way to the hospital.

She had had a placental abruption, a condition in which the placenta detaches prematurely from the uterus. The resulting loss of oxygen and glucose to the baby's brain caused a condition called hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Doctors quickly delivered baby Sianna Marie Acevedo by Caesarean section. But she wasn't breathing. In fact, she didn't breathe for about 14 minutes. Her little heart pumped at just 30 beats a minute — much slower than the 100 to 160 beats a minute considered normal for newborns. She was pale and wasn't moving.

"I broke down. I thought I had lost my child," Miguel Acevedo says.

Within the hour, Sianna was on her way by helicopter to Shands at UF. There, neonatologist Michael Weiss, M.D., and his team in the neonatal intensive care unit have been using a body cooling technique to try to stave off damage to the brains of babies like Sianna.

Weiss and his team started quickly to carry out the procedure, called systemic hypothermia. They placed the baby on a pad attached to a temperature control machine, cooling her body to about 7 degrees Fahrenheit lower than normal body temperature for 72 hours. EEG electrodes attached to her head allowed monitoring of her brain activity patterns that could give clues about how she will fare after the treatment. A cerebral saturation monitor, connected to the lead on the baby's forehead, gave Weiss an idea of blood flow to the brain. UF is one of the few institutions to use this monitor and one of the few in the state to offer the cooling procedure.

Before 2004, when babies with diagnoses like Sianna's came in, all doctors and nurses could offer was "supportive care" — such as monitoring the baby's blood pressure and glucose levels, checking that the kidneys are working properly and stanching any bleeding.

"There was nothing we did that was geared at minimizing the amount of injury the brain had," Weiss says.

Now, even though the cooling procedure is available, it is not universally used. Weiss is trying to change that by teaching colleagues at other hospitals about the technique.

He and other health professionals and researchers at UF and Shands continuously seek out new ways to help patients, often when there are no alternatives. In so doing they help to make UF and Shands a fertile ground for development and use of new medical technologies, whether it's using brain-saving cooling protocols, developing new vaccines or exploring new applications for robot-assisted surgery.

UF neonatologist Dr. Michael Weiss used a new cooling technique on newborn Sianna Acevedo, who was deprived of oxygen during birth, to help stave off brain damage. The white pad underneath her is used to regulate her temperature.

"I think UF has a lot of highly intelligent investigators who are working to get new therapies to patients," says Johannes Vieweg, M.D., chair of the department of urology, which has a division of robotics and minimally invasive surgery. "We want to be known as a hub for innovative therapies."

New initiatives such as UF's Clinical and Translational Science Institute and the Florida Innovation Hub serve to foster a culture of technology and invention and speed new discoveries to patients.

Weiss has treated 10 babies with the cooling procedure in the two years since he started offering it. Now, he is trying to help even more babies around the state. He is applying for a grant from the CTSI to develop the Florida Neurologic Network, a collaboration among the UF and Shands hospital system and other academic and private hospitals in North Central Florida that aims to improve the hypothermia technique, instruct other doctors on its use and make it more widely available.

"To me that's really exciting to be able to get it out to more people," says Chris Batich, Ph.D., associate director of the CTSI, who works to bring physicians into collaborations with engineers, scientists and other experts who can turn research ideas into technologies that can help even the littlest of patients, like Sianna, and bring them into widespread use.

Whether it's in caring for newborns or helping people struggling with infertility, new technology at UF is giving people hope.

The robot is in

Robot-assisted surgery, which came into use in the United States in 2001, has enhanced treatment offerings and outcomes for patients. Robotic surgery allows surgeons to operate through small incisions in the body. That helps reduce recovery time, blood loss, postsurgery pain and scarring compared with so-called "open surgery" in which large incisions are made in the body to remove diseased tissues and organs.

Robot-assisted surgery gives surgeons a high-definition view that can be magnified up tp 12 times. The robot also allows surgeons to make more precise cuts.

In robotic surgery, the surgeon uses joysticks to operate the robot remotely from a console a few feet away. The surgeon also "drives" the robot using gearshifts and foot pedals, making surgical movements the robot mimics. The four arms hold small surgical and monitoring instruments. With its many mechanical joints, the computer-driven robot allows easier access to hard-to-reach areas of the body. The machine eliminates hand tremor and excessive movement by refining the surgeon's wrist movements, scaling them down to one-fifth of the normal motion.

A telescopic binocular lens gives surgeons a sharp, high-definition 3-D live view that is magnified up to 12 times. That allows them to anticipate bleeding earlier and minimize blood loss. They can also cut more carefully in a way that preserves muscles, nerves and other tissues near the surgical area.

"The way to think about robotic surgery is as an extension of a skill set surgeons already have," says Li-Ming Su, M.D., chief of robotic and minimally invasive urologic surgery in the College of Medicine. "If we can see better, then we can perform better and more precise surgery."

Robotic surgery is employed in a variety of disciplines, including pediatrics, cardiology and gynecology. But it's urology where the technology seems to have taken off, sprouting a host of applications. UF's urology department has five surgeons with advanced fellowship training in robotic surgery.

Sijo Parekattil, M.D., for example, uses the robot for microsurgical treatments — intricate surgery on small body structures — in applications such as testicular sperm extraction, tying off varicose veins within the testicles, vasectomy reversal and treating chronic testicular pain. He has performed more than 100 robotic microsurgical procedures.

Parekattil, director of male infertility and microsurgery in the urology department, is presenting his work later this year at the World Congress of Urology in Munich.

In women, robotic surgery can help correct vaginal prolapse — a condition in which organs such as the bladder, bowels or uterus protrude into the vaginal canal because of the failure of support structures within the pelvis. That can occur as a result of childbirth, pregnancy, aging or other factors. Through five small incisions in the abdomen, Louis Moy, M.D., director of female urology and reconstructive surgery, robotically creates new support for the vagina and pelvic organs with a synthetic mesh anchored to the bony part of the pelvis.

"It's really no different from open abdominal surgery, just less invasive," Moy says.

All the better to see you with, my dear

Robots have dramatically improved surgeons' ability to see what they are doing. Su is taking the technology a step further in order to improve the visibility of hard-to-see tumors deep within the kidneys.

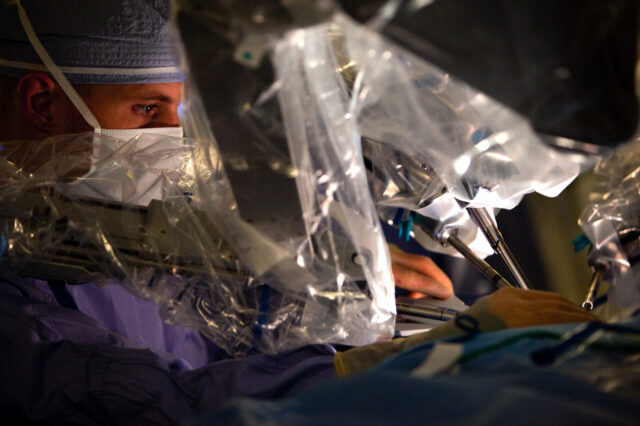

In robotic surgery, surgeons operate the robot from a console a few feet away from the patient. Here, medical resident Dr. Bryant Whiting assists during one of urologist Dr. Sijo Parekattil's surgeries.

"If you can't see it, where do you cut?" Su says.

He's trying to solve that riddle using a technique called augmented virtual reality, which involves creating 3-D images of the kidney from MRI and CT scans, and overlaying them in real time on the surgeon's robot-eye field of vision.

"It essentially provides a road map of where to cut," he says.

Now, he is trying to develop collaborations with UF mechanical and bioengineers to establish a multidisciplinary team to bring the idea to fruition.

To give gastroenterologists a live camera view — rather than an indirect X-ray view — in difficult procedures involving narrowing or large stones in the gallbladder, bile ducts, pancreas, and liver, Peter Draganov, M.D., and Chris Forsmark, M.D., chief of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, collaborated with Boston Scientific during development of a technique called direct visualization cholangioscopy. UF was the first in the nation to have it after its 2006 FDA approval.

Don't make a hole

While robotic surgery and other minimally invasive surgical techniques aim to make small incisions and leave the smallest scars possible, other techniques aim to leave no scars behind.

When it comes to avoiding scars, a new technology called the NanoKnife is a master. Applied in the treatment of conditions such as liver, lung and kidney disease, it kills lesions in soft tissue without damaging surrounding structures such as blood vessels and nerves. Only about 20 institutions around the world offer this technology, and UF has been given the option to have it too.

NanoKnife surgery involves shocking cells of lesions with electrical currents supplied by tiny electrodes. That causes the cells to open and lose the key components needed for life. Those cells die a natural death and are cleared away and replaced by the body's healing processes, leaving no scars.

"This technology has much less collateral damage than other techniques that we use, and in addition, it's faster," says James Caridi, M.D., chief of the division of vascular and interventional radiology.

Another UF gastroenterologist is researching no-scar surgery through already existing body openings such as the mouth, rectum, vagina or urethra. This "natural orifice" surgery involves making incisions inside the gastrointestinal or reproductive tract to get to other organs. That goes against traditional medical training and practice.

"‘Don't make a hole' — that's what we've been taught and that's what's in our textbooks, but now that may change," says Mihir Wagh, M.D., an assistant professor in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition.

Unintentional perforations in the GI tract can be dangerous, causing its contents to leak into the chest or abdomen.

But in animal studies, Wagh has intentionally made holes in the stomach and colon to remove the uterus, ovaries and gallbladder, then closed the holes from inside, leaving no external scars. Wagh has presented his work at national and international meetings — in October he will present in Germany.

Many questions — medical and otherwise — surround the technique. Who should perform it — a gastroenterologist? A gynecologist? A surgeon? How would practitioners be trained? And would insurers cover the novel procedures?

Various centers around the United States and around the world are studying this type of surgery in humans and animals. Wagh is also investigating whether surgery complications such as unintentional damage or excessive bleeding can be fixed through the same orifice used for the surgery.

"We're just at the basic infant steps right now," he says.

While researchers nurture their discoveries to maturity, the Acevedos are looking forward to seeing their daughter take her first steps.

°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°°

Kalipay Acevedo had to wait in recovery for three days after her delivery. But as soon as she was discharged from the Tampa hospital where she gave birth, her husband drove her to the NICU at Shands at UF. She wept as she came through the doors.

"I expected tubes to be everywhere and her head to be swollen, and I expected her to be smaller," she says.

But although Sianna had been connected to a ventilator earlier, now she was breathing on her own. Her skin looked healthy. She was moving and making little purring noises that made her dad, Miguel, laugh out loud.

"This is night and day compared to what she was two days ago," he says.

In just a few hours, doctors would start warming Sianna up — very slowly, by just over half a degree Fahrenheit per hour. Then they would wait and see what happens in the coming weeks, months and years.

"This is the toughest thing for a family," Weiss says. "You can't tell the parents exactly how they're going to turn out two or three years from now."

But for the Acevedos, it was enough that the UF and Shands doctor and nurses had tried.

"Just having an option of something that you can do instead of all the negative things — it just gives me that hope," Kalipay Acevedo says."I was so thankful that they didn't give up on her."