EGD - esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Definition

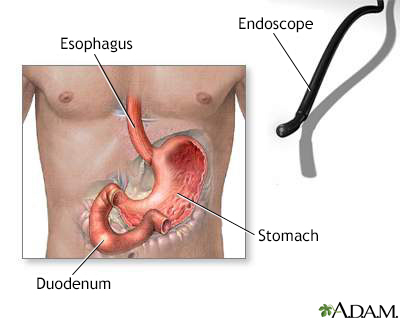

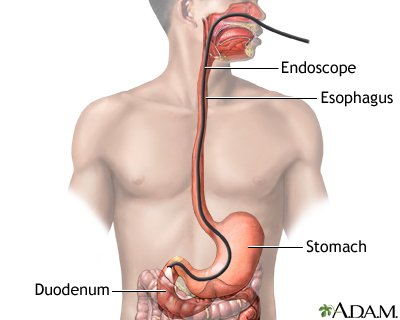

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a test to examine the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine (the duodenum).

Alternative Names

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; Upper endoscopy; Gastroscopy

How the Test is Performed

EGD is done in a hospital or medical center. The procedure uses an endoscope. This is a flexible tube with a light and camera at the end.

The procedure is done as follows:

- During the procedure, your breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen level are checked. Wires are attached to certain areas of your body and then to machines that monitor these vital signs.

- You receive medicine into a vein to help you relax. You should feel no pain and not remember the procedure.

- A local anesthetic may be sprayed into your mouth to prevent you from coughing or gagging when the scope is inserted.

- A mouth guard is used to protect your teeth and the scope. Dentures must be removed before the procedure begins.

- You then lie on your left side.

- The scope is inserted through the esophagus (food pipe) to the stomach and duodenum. The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine.

- Air is put through the scope to make it easier for the doctor to see.

- The lining of the esophagus, stomach, and upper duodenum is examined. Biopsies can be taken through the scope. Biopsies are tissue samples that are looked at under the microscope.

- Different treatments may be done, such as stretching or widening a narrowed area of the esophagus.

After the test is finished, you will not be able to have food and liquid until your gag reflex returns (so you do not choke).

The test lasts about 5 to 20 minutes.

Follow any instructions you're given for recovering at home.

How to Prepare for the Test

You will not be able to eat anything for 6 to 12 hours before the test. Follow instructions about stopping aspirin and other blood-thinning medicines before the test.

How the Test will Feel

The anesthetic spray makes it hard to swallow. This wears off shortly after the procedure. The scope may make you gag.

You may feel gas and the movement of the scope in your abdomen. You will not be able to feel the biopsy. Because of sedation, you may not feel any discomfort and have no memory of the test.

You may feel bloated from the air that was put into your body. This feeling soon wears off.

Why the Test is Performed

EGD may be done if you have symptoms that are new, cannot be explained, or are not responding to treatment, such as:

- Black or tarry stools or vomiting blood

- Bringing food back up (regurgitation)

- Feeling full sooner than normal or after eating less than usual

- Feeling like food is stuck behind the breastbone

- Heartburn

- Low blood count (anemia) that cannot be explained

- Pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen

- Swallowing problems or pain with swallowing

- Weight loss that cannot be explained

- Nausea or vomiting that does not go away

Your doctor may also order this test if you:

- Have cirrhosis of the liver, to look for swollen veins (called varices) in the walls of the lower part of the esophagus, which may begin to bleed

- Have Crohn disease

- Need more follow-up or treatment for a condition that has been diagnosed

The test may also be used to take a piece of tissue for biopsy.

Normal Results

The esophagus, stomach, and duodenum should be smooth and of normal color. There should be no bleeding, growths, ulcers, or inflammation.

What Abnormal Results Mean

An abnormal EGD may be the result of:

- Celiac disease (damage to the lining of the small intestine from a reaction to eating gluten)

- Esophageal varices (swollen veins in the lining of the esophagus caused by liver cirrhosis)

- Esophagitis (lining of the esophagus becomes inflamed or swollen)

- Gastritis (lining of the stomach and duodenum is inflamed or swollen)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (a condition in which food or liquid from the stomach leaks backwards into the esophagus)

- Hiatal hernia (a condition in which part of the stomach sticks up into the chest through an opening in the diaphragm)

- Mallory-Weiss syndrome (tear in the esophagus)

- Narrowing or stricture of the esophagus, such as from a condition called an esophageal ring

- Tumors or cancer in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum (first part of small intestine)

- Ulcers, gastric (stomach) or duodenal (small intestine)

Risks

There is a small chance of a hole (perforation) in the stomach, duodenum, or esophagus from the scope moving through these areas. There is also a small risk of bleeding at the biopsy site.

You could have a reaction to the medicine used during the procedure, which could cause:

- Apnea (not breathing)

- Difficulty breathing (respiratory depression)

- Excessive sweating

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Slow heartbeat (bradycardia)

- Spasm of the larynx (laryngospasm)

Gallery

References

Koch MA, Zurad EG. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. In: Fowler GC, ed. Pfenninger & Fowler's Procedures for Primary Care. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 91.

Sugumar A, Vargo JJ. Preparation for and complications of GI endoscopy. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 42.